Article by David Papini and Julia Stewart.

Julia: Below is the winning entry in the Best Coaching Films Contest. I chose it, not because it was the best example of coaching, but because it was presented in a thorough manner that made it easy for David Papini and me to analyze it, which we were interested in doing. In that sense, it's an awesome entry and it provides a terrific opportunity to disect something that sounds like coaching, but actually isn't. At least it's not very good coaching. See if you agree.

You may or may not be surprised to know that the character of John Keating, in Dead Poet’s Society, is not an example of a good coach. Yes, he opens up new worlds for his students, something that great coaches do, but he is burdened by enormous assumptions and a huge agenda, which leads him to a crucial conversation with Neil Perry and may have helped cause Perry’s later suicide. Not a desirable outcome in coaching!

Actually, this film is a wonderful example of what happens when Values Systems collide. It ain’t pretty. The parents and teacher’s are all of the modern values system: rational, materialistic, conforming. Think: Business Executives. (And read Spiral Dynamics or take our Spiral Dynamics for Coaches course, if you don’t know what I’m talking about.) Keating’s values are post-modern: creative, individualistic, passionate. Think: Hippies.

There is nothing wrong with either system, but in evolutionary terms, post-modern comes after modern, which makes it more inspiring (that’s just how it works). Keating and his student’s assume that ‘inspiring’ is better. However, the only thing that makes one Values System better than another is whether it solves your problems best.

The film, itself, is passionate and can inspire and trigger the viewers’ own adolescent memories of struggling to become authentic while being pushed and bullied to conform by parents and teachers. But for one very sensitive, vulnerable, conflicted boy, Neil Perry, who is the ‘client’ in the following ‘coaching’ session, this schism presents a problem so overwhelming, he pays the ultimate price.

David: I think that here Keating is not coaching Neil, he is more trying to help him as parent would do. One of the risks of a “parenting” coach model is that parenting brings with itself not just love and care but it is also prone to confusion between parent’s needs and child’s needs. This kind of confusion has an evolutionary advantage, because maximizes the chances that a parent will take care of her children as if they were herself, but it is not that useful when your goal is to foster someone else’s freedom of choice.

In terms of technique, Keating here uses more the tools of a tutor or mentor. All the relationship is with Keating ‘up’ and Neil ‘down’. No doubt, Keating cares about Neil’s greatness, but he fails in checking and validating if the change that he is pushing Neil through is ecological for all Neil’s parts. Working with all the parts (for example with NLP) and allowing all of them to show what their good intention was and to foster dialogue among them, could have been useful to Neil.

Read on to see why a coach’s assumptions and agenda can cause a client his very life...

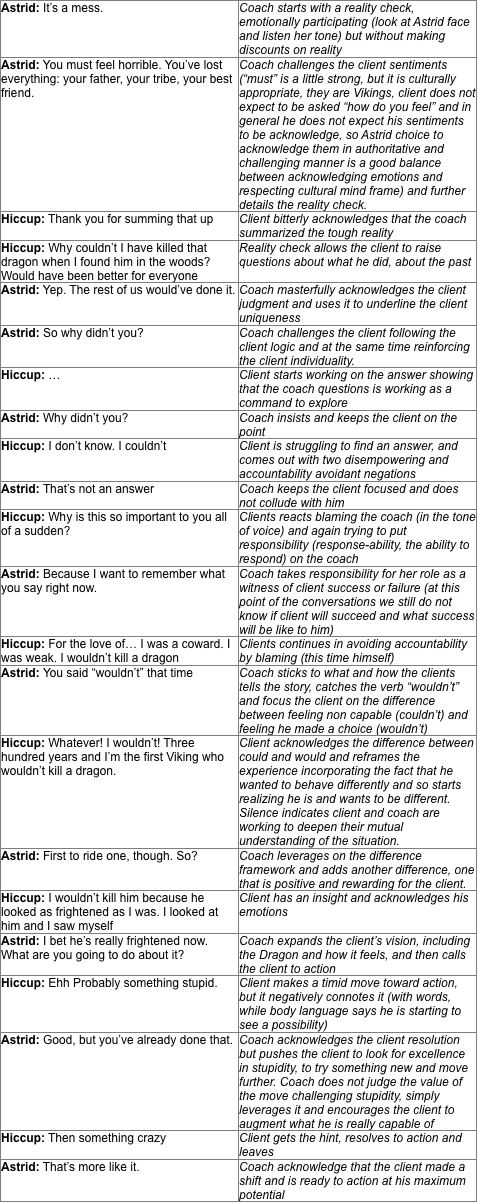

John Keating Coaching Neil Perry:

|

Coaching Conversation |

Analysis |

|

Neil Perry: I just talked to my father. He's making me quit the play at Henley Hall. Acting's everything to me. I- But he doesn't know! He- I can see his point; we're not a rich family, like Charlie's. We- But he's planning the rest of my life for me, and I- He's never asked me what I want! |

David: Here Neil shows he is aware of what is really important to him and also he is capable of understanding his father’s reasons and he is also aware that his father is not recognizing him as a person capable of choice Julia: Neil’s dilemma is fairly typical of a coaching client’s presenting problem, even though his is the perspective of a minor. His story is highly emotional and full of assumptions. He’s genuinely stuck. |

|

John Keating: Have you ever told your father what you just told me? About your passion for acting? You ever showed him that? |

David: Keating clarifies, acknowledge Neil’s passion and invite the possibility for Neil to share more with his father Julia: Great coaching question from Keating. It not only elicits important information, but points to a possibly more resourceful response to Neil’s problem. |

|

Neil Perry: I can't. |

David: Neil is facing a block. Julia: This is a typical response from someone who is stuck. There is no physical reason that he can’t talk to his father, but he believes he can’t. |

|

John Keating: Why not? |

David: Keating poses an ineffective question. He could have asked about Neil feelings (how does it feel that you cannot share with your father) or add resources (what would you need to be able to tell him). The “why” question here seems to hide Keating’s agenda or a tutorial question (I know you can and I want you realize that). Keating here is acting like a parent, a tutor, a mentor or a friend more than a coach. Julia: I agree with David. Questions that begin with ‘why’ tend to invite rationalization from the client, which just deepens the story and the client’s sense of having no options. To open Neil’s mind to more options and resourceful thinking, Keating could try the following questions: ‘What would it be like if you could talk about this with your father?’ ‘What would you tell him, if you could?’ ‘Would you like to be able to talk with him about what’s really important to you?’ |

|

Neil Perry: I can't talk to him this way. |

David: Neil is still blocked but adds “this way”. Julia: Neil doesn't have the words to articulate what's holding him back, he just knows he's stuck. |

|

John Keating: Then you're acting for him, too. You're playing the part of the dutiful son. Now, I know this sounds impossible, but you have to talk to him. You have to show him who you are, what your heart is! |

David: Coach here had the opportunity to clarify (for example asking “what way”?). Keating choses to challenge and show Neil his intuition (“You’re acting for him, too”), without asking for permission to share. Then uses all of his influence to push Neil toward the behavior he considers appropriate (he asks Neil to do something that seems impossible to Neil and possible to the idea that Keating has of Neil’s strength and of Neil’s relationship system). Keating shows love for Neil but it’s not a loving coach act, again, it’s more a mentor’s or a tutor’s action, who sees the reality of his pupil’s behavior Julia: Agreed. Although Keating's aware of Neil's assumption, he's not aware of his own. He's pushing Neil toward the outcome that Keating believes in. Neil needs to decide what’s best for himself. Even though Keating is a mentor/instructor to this young man, he’s over-stepping his professional boundaries. This would be considered unethical in coaching. The fact that Neil later commits suicide is strong evidence that this conversation didn’t serve him. |

|

Neil Perry: I know what he'll say! He'll tell me that acting's a whim and I should forget it. They're counting on me; he'll just tell me to put it out of my mind for my own good. |

David: Neil is still blocked. His options are not increased, he is still trapped in a scene he already knows. Julia: Neil is quite naturally resisting the push that Keating gives him. Most coaching clients will push back in similar ways when pressured by their coaches. |

|

John Keating: You are not an indentured servant! It's not a whim for you, you prove it to him by your conviction and your passion! You show that to him, and if he still doesn't believe you - well, by then, you'll be out of school and can do anything you want. |

David: Keating acknowledge the genuineness and the importance of Neil ‘s passion, but again offer to him solutions that do not come from Neil himself and assumes that proving the passion to the father will be useful for Neil (implicitly reinforcing the idea that the father has to decide). Also the second option (you can do what you what when you leave school) is completely part of Keating mindset. Here Keating is consulting (giving advices) and/or leading (ordering). The coaching part could have been the first one, if the sentence finished with “it’s not a whim for you”. On another layer of thought here there could be also that Keating is fighting with Neil’s father (what Neil’s father represents to Keating), by using Neil as means. Keating here is acting like Neil’s father, forgetting that Neil already have one that tells him what to do. The fact that the real father is not capable of loving Neil enough, does not authorize Keating to use a father role as a way to take care of Neil’s needs, especially without acknowledging the conflict that will rise in Neil’s emotions. Julia: Keating is pushing his own Values System on Neil, something that he did throughout the film, with mixed results for the boys. He awakened something inspiring in them, but assumed parents and teachers would value it. They didn’t, which created conflict for all the boys. By the way, Keating’s Value System is Green, or post-modern, in integral terms. The school and parents were mostly operating at the Blue/Orange, or traditional-modern level, which does not understand Green. Post-moderns typically make this mistake, that everyone will see the wisdom of their view, if just given the chance. They won’t. Again, this is unethical in coaching. Don’t make this mistake for your own clients. |

|

Neil Perry: No. What about the play? The show's tomorrow night! |

David: Neil assumes for a moment the second Keating’s suggestion and confronts it with the practical short term consequences, and has a doubt. Julia: More resistance in response to being inappropriately pushed. |

|

John Keating: Then you have to talk to him before tomorrow night. |

David: Keating provides the answer, completely in the frame of his agenda (Neil must talk with his father) Julia: If Keating were a good coach, someone who cares more for others than for his own agenda, he would have elicited options from Neil and respected them. Or at the very least, offered multiple options, rather than telling Neil what to do. |

|

Neil Perry: Isn't there an easier way? |

David: Neil asks for a way to avoid something he fears. Julia: Keating would do well to respect the wisdom behind Neil’s reluctance. |

|

John Keating: No. |

David: Keating acknowledges the fear (by non-verbal cues, need to see the scene ;-) but keeps Neil on the decision (which is not Neil’s decision). If Neil’s fear had arrived after a personal insight or search path, this could be an appropriate way to keep the client on track, but given the previous choices made by Keating in the conversation, it’s just another way to push Neil to realize Keating’s agenda (which of course Keating considers an agenda for the good as Neil’s father does with his one, and this is often the tragedy…) Julia: Rather than eliciting greatness from Neil and helping him expand his possibilities, Keating’s ‘coaching’ arrives at one very narrow and unproductive option. |

|

Neil Perry: [laughs] I'm trapped! |

David: Neil is emotionally trapped (and desperate) Julia: Neil is between a rock and a hard place, with his father’s values on one side and Keating’s on the other. As a teenager, he hasn’t yet developed the strength to think for himself and has allowed Keating to back him into a corner. Some adult coaching clients are also this easy to influence. Coaches need to be extremely careful not to make decisions for our clients. We never have all the information. We’re only there to help the client think better and to inspire their personal greatness. |

|

John Keating: No you're not. |

David: Keating does not acknowledge the emotions in Neil, and underlines that Neil is free. Julia: Yes, in Keating’s mind, Neil is free, but only IF Neil does what Keating tells him. This is an obvious contradiction, common to post-modern thinking. It’s all about a specifically defined form of liberation that is ultimately repressive: ‘You’re free if you do what I tell you to do.’ Post-modern thinking is common among coaches, but often results in narrow thinking. My personal bias is that post-modern thinking has limited value in coaching. |